See also a post about the Dead and electronic music.

Whenever I play guitar, it comes out sounding like Jerry Garcia. I can’t help it. From the ages of fifteen to twenty, my guitar-learning years, there was no musician I cared more about in the world than Jerry. Contrary to popular stereotype, I didn’t care about him because of drugs. I listened to the Grateful Dead for years before ever trying drugs of any kind. I just really liked the music.

Jerry was a groove player

The biggest lesson Jerry taught me was the value of beats you can dance to, at slow to medium tempos, using minimal harmonic movement. Jerry did his best playing over relaxed one-chord or two-chord Afrocentric grooves with a free jazz flavor. Jerry also played okay country and white R&B, and he occasionally rocked. But mostly he was devoted to trance-like grooves.

I went to see the Dead several times in high school, and a few increasingly depressing times my freshman year of college. Jerry was completely phoning it in at that point, and the rest of the guys performed unevenly at best. And yet, those shows were still fairly magical experiences. There was a lot of audience participation, group singing and dancing and clapping. I’m a nerdy white guy, and I spend a lot of time alone or with strangers. I don’t do a lot of group singing and dancing and clapping. Those activities are essential social vitamins, and I feel the absence of them in my life. Dead shows could be messy and lame, but they were a reliable source of tribal-feeling ecstatic experience. In interviews, Jerry frequently compared his following to a religious cult. If church was more like a Dead show, I’d probably go.

The best thing the band did during the years I went to see them was to close their shows with “Not Fade Away” by Buddy Holly. The song is a modal I7-IV groove over a distinctive beat: clap, clap, clap, clap-clap; clap, clap, clap, clap-clap. It’s an Afro-Cuban pattern called son clave, which rock musicians know as the Bo Diddley beat. Over the course of “Not Fade Away,” the Dead effectively taught the entire crowd to clap son clave. During the very extended tag out, while singing “Love is real, not fade away” over and over, the band would pull the volume back quieter and quieter until all you could hear was the crowd’s clapping and singing. Then they’d simply wave goodnight and walk offstage as the crowd continued. I remember one show at Giants Stadium in high school, the crowd kept the chant going all the way down the ramps and across the parking lot. Powerful!

The Dead weren’t a good band, but they were a great one

The Dead didn’t try very hard to be liked. They could never be bothered to sing in key. They wrote convoluted arrangements and didn’t rehearse them, so they routinely trainwrecked. The music was ad-hoc and messily indifferent a lot of the time. Some of the lyrics are pretty, but a lot of them are empty stoner poetry.

And yet. For brief intervals during their long and checkered career, the Dead could be the greatest band in the world. At their best, they were daring and inventive, capable of performing dazzling feats of group improvisation. Their frequent risk-taking necessarily involved a lot of failure, but it also made for some big musical successes. The high points are widely scattered, but the Dead played for so many years that they managed to rack up a good number of them.

The Dead as viral marketing pioneers

The good news for fans is that searching for the Dead’s magic moments is extremely easy. Just about every public note that Jerry and company ever played is meticulously archived and available. The professionally-mastered high points can be downloaded commercially, and the band allows the rest to circulate for free.

From the beginning, the Dead had a famously relaxed attitude toward concert taping. At shows there was a special seating area reserved for tapers, who were invited to plug their gear directly into the soundboard for maximum recording quality. Jerry was inspired by a similar custom at the bluegrass festivals he attended as a young guy. This practice of encouraging people to tape Dead shows started out as a bit of hippie idealism, but it turned out to be a brilliant viral marketing strategy.

In high school, one of my most treasured possessions was my cassette copy of 5/8/77 set II with its labels in my friend Ellie’s handwriting. The encore cut off halfway through. A lot of tapes like this circulated through the hands of obsessive fans like me, spreading the music through word of mouth, until the Dead suddenly emerged in the 1980s as one of the biggest moneymakers in the live music industry.

The concert tape trading network got a lot more efficient once it got hold of the internet, but even before the web, it was surprisingly robust. Using snail mail and word of mouth, it was possible to get your hands on pretty much any of the most widely-traded shows. You sent blank cassettes off to a stranger in padded mailers with return postage, and a few weeks later, there would be your fresh tapes. It was like a very slowly-paced mp3 blog. The Dead’s fan base was never very big compared to that of the Stones or the Beatles, but it was deep, and devoted. By insisting on giving away so much of his recorded music for free, Jerry died much wealthier than he was born.

The image of no image

The Dead’s popularity peaked at a time when they were the least telegenic bunch of musicians imaginable. They were middle-aged, homely, and wildly uncharismatic. Onstage, Bob Weir made an effort to look alive, move around, and engage the crowd a little, but the rest of the band just looked at the floor, Jerry especially. The Dead’s pointed indifference to their appearance was a big part of what drew me into listening to them in the first place. I figured that they must have been seriously badass to have so much celebrity with so little image. I didn’t yet understand that lack of image is itself an extremely compelling image.

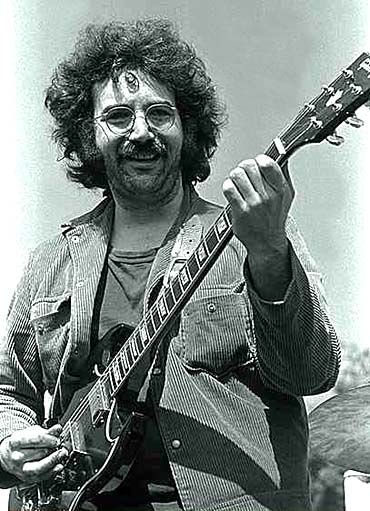

Here’s how I remember Jerry looking those years I was going to shows.

Jerry tried to discourage people from thinking of him as a cult leader, but without success. Americans are suckers for a messianistic beard. The New Yorker once aptly described Jerry as resembling “an unmade bed.” Other likenesses: Santa Claus, Gandalf, Jesus, a grandpa, a caveman, a guru, a homeless person, a hermit. The main thing Jerry looked was: old. He was only fifty-three when he died, but due to his hard living, he looked more like eighty-three. Jerry may not have been the first geriatric rock star, but he most looked the part. He’s the only major rock star I can think of who became more popular and influential as his hair got whiter.

Jerry’s wardrobe was mostly limited to black t-shirts, with black sweats or black jeans. The rest of the band were similarly not fashion-conscious. Phil Lesh performed in red-white-and-blue wristbands, a tie-dyed t-shirt tucked into khaki slacks, and running shoes. Taken together, the late-period Dead looked like my parents’ friends, or the English department at a small liberal arts college.

This photo comes from the liner notes to In The Dark, which contains the Dead’s one and only top ten hit song, “Touch Of Grey.” The phrase perfectly describes both the band and their core fan base.

Iconography

As people, the Dead may not have been very image-conscious, but they had exquisite taste in graphic designers. The band’s killer logo is called the Stealie, so named because it appeared on the cover of the Steal Your Face album. It’s a dreadful record, possibly the band’s worst, but it’s an amazing cover.

The logo was designed by the Dead’s sound engineer and in-house LSD provider, Owsley “Bear” Stanley. He devised it for stickers that he put on the band’s equipment, making it easier to tell it from the other bands’ gear in dark backstage areas.

Why did I constantly draw Stealies on my high school notebooks? For one thing, it’s fun to draw. It’s an easy little visual algorithm to memorize, but you have to really pay attention to get the execution right. It looks dangerous yet friendly, ancient yet modern, funny yet sinister, symmetrical yet asymmetrical. It’s a play on the American flag, the bones of the head, the lightning strike of inspiration. Its meaning is, as my shrink would say, multiply-determined.

The Stealie is a stupendously successful meme. You can put anything inside the circle in place of the lightning bolt: a dancing bear, a turtle, Jerry’s face, the name of your frat. Some clever person did a t-shirt that had an infinitely recursive series of smaller skulls-within-skulls. The skull can anchor all kinds of cool new designs and adventurous typography, too.

I was exposed to the Dead’s visual iconography long before I heard any of the music. My stepbrother stored a bunch of his records in our apartment’s closet when I was growing up, and eventually I got curious and started poking around them. Along with the Allman Brothers and Steely Dan, there were a couple of Dead albums whose covers practically radiated menace.

Based on the skull imagery, I expected death metal, so imagine my surprise when I finally put one of these records on and found it to be agreeable spacy jazzy-country-rock. Here’s a much less frightening album cover, from Europe ’72, a Stanley Mouse painting nicknamed Ice Cream Boy:

I get a MAD Magazine vibe from this image, Don Martin meets R Crumb. Jerry was an avid MAD reader as a kid, as was I.

Along with eye-catching album covers and t-shirts, the Dead also put out some gorgeous books. A standout: this book of hand-lettered transcriptions of every tune on American Beauty and Workingman’s Dead:

The Dead’s music

What sets jam bands apart from the rock mainstream isn’t so much the jamming — every flavor of halfway decent American music has improvisation. Jam bands, the Dead in particular are distinctive for their loose, laid-back, non-urgent feel, a vibe that has more in common with jazz or country than rock.

The Dead didn’t kick much ass, but there are things you can do other than kick ass. For such a big lumbering animal, the band could play remarkably quietly. On ballads like “He’s Gone” or “High Time,” they could bring two electric guitars, a six-string bass, one or two keyboards, and one or two full drum kits down to total silence at the end of each measure, in a stadium packed with people. This is no small accomplishment. Playing loud and hectic is easy; playing restrained and quiet is hard. The Dead could play slower and quieter than any other rock band I can think of. Ask any musician how tough it is to play slow tempos without losing energy. The ambling pace annoyed me as a teenager, but the older I get, the more sense the unhurried, conversational tone makes.

Jerry’s guitar style

The musical story of the Grateful Dead is a series of snapshots of Jerry’s psyche, variously bouyed and hindered by his bandmates, variously bouyed and hindered by himself. The mid-seventies were a crisis point for the band, the closest they came to breaking up, and the consensus is that they never recovered. But I have a particular fondness for the Dead’s music of this period. The bloom was off the rose by that point, as the band slid from hallucinogens into cocaine, heroin and alcohol, but they still had the essential sound together. The tempos were nice and rubbery, the emphasis was on groove and polyrhythm, and when Jerry was paying attention, he did some of his best playing during the long, languid jams and grooves.

Jerry’s greatness as a guitarist isn’t a matter of technical skill. He had good chops by rock standards, but he was no virtuoso. What he had going for him was touch and phrasing. He massaged and squeezed individual notes into curvy microtonal shapes, in a style informed by his pedal steel playing. (Jerry’s most-heard recording is probably his pedal steel part on “Teach Your Children” by Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young.) Rockers tend to lean ahead of the beat, but Jerry played behind the beat, sometimes way behind. Again, this was due to his close study of jazz and country. His tone was mostly clean and undemonstrative, sometimes even hesitant. Guitar heroes playing to packed stadiums aren’t usually so quiet and unobtrusive.

Jerry’s improvising was harmonically adventurous, spiced with ninths, elevenths, and thirteenths. He used a lot of intentionally “wrong” notes, like the natural seventh against dominant seventh chords. He wasn’t a jazz guitarist per se, but he had some of that vocabulary under his fingers. For example, he sometimes deployed an angular diminished scale lick that he must have learned straight from John Coltrane. Jerry was a tremendous music dork with keen insight into his own approach. See, for instance, this terrific interview in Guitar Player, in which he compares improvisation to assembling a jigsaw puzzle with all white pieces.

Maybe even more valuable than his original work was Jerry’s ability to synthesize seemingly disparate sources into idiosyncratic new ideas. He drew inspiration not just from rock, but from R&B, blues, swing, bebop, free jazz, bluegrass, assorted world musics, ragtime, and even electronica — Jerry loved controlling synths with a MIDI guitar. He would have been an incredible music blogger or DJ, and his interviews are an excellent guide into the more obscure corners of American music. For instance, he evangelized Elizabeth Cotten and covered several of her tunes, both with and without the Dead. Do yourself a favor and check her out, she’s one of my favorite guitarists ever.

Jerry’s recommendations also led me to Howlin’ Wolf, Peter Tosh, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Robbie Robertson, Bill Monroe and Carlos Santana.

Jerry and depression

The skull imagery on the album covers was not accidental. The Dead derived a lot of their power from their surprising nihilism. Jerry mentioned at one point that the name Grateful Dead was specifically chosen to “repel curious onlookers.” Forget the dancing teddy bears; think of the fact that Jerry wore all black, all the time. Other jam bands have Jerry’s amiable eclecticism, but they lack his sinister edge. Bands like Phish prefer to evade the despair at the core of hippiedom, but ignoring the darkness of the sixties misses the point of that troubled and turbulent period of our nation’s history.

I was saddened but not surprised to learn that Jerry had a troubled inner life. He was five years old when his father drowned, and he had a difficult relationship with his mother and stepfather. He was married many times, never happily, and he was visibly indifferent to his own health and well-being. He self-medicated his depression with a variety of increasingly ineffective hard drugs, and spent his final years using heroin almost continuously. Maybe Jerry thought he was using heroin and cocaine for pleasure, but it looks more to me like a gradual suicide.

The band suffered many casualties besides Jerry. Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, the Dead’s original frontman, drank himself to death at age twenty-seven. Keyboardist Keith Godchaux died in a motorcycle accident shortly after quitting the band. His replacement, Brent Mydland, capped off a longstanding cocaine addiction with a fatal overdose. His replacement, Vince Welnick, committed suicide a few years after the rest of the Dead re-formed post-Jerry and edged him unceremoniously out.

In interviews, the Dead come across as spectacularly misanthropic, Bob Weir and Phil Lesh in particular. At no point did the Dead ever convey themselves as a bunch of people you’d want to hang out with. They made a good-faith effort to help the paying customers have a good time, but their music was frequently impersonal, emotionally closed-off and inaccessible.

But Jerry’s playing had a way of transcending his environment. The best musicians take tragedy and transform it into pleasure. Jerry matters to me because he was an extremely unhappy person who nonetheless created music that has made uncountably many people happier. Really, what greater contribution to humanity could you ask for?

Recommended listening

All of the shows by the Dead and Jerry’s various side projects are archived here. Here are some recommended high points:

2/28/69 Fillmore West

2/13-14/70 Fillmore East

5/2/70 Harpur College

12/31/71 Winterland Arena – check out “Space” -> “Other One”

4/8/72 London, England – check out “Dark Star” -> “Caution.”

8/24/72 Berkeley, CA

9/27/72 Stanley Theater — “Dark Star” segues smoothly and spontaneously into “Cumberland Blues,” an amazing display of group cohesion.

12/19/73 Tampa, FL — dig “Playing In The Band.”

2/23/74 and 2/24/74 Winterland Arena — The first one is slow to get going, but once they’ve warmed up, wow. The second one pretty much kills all the way through.

5/8/77 Cornell U — a Deadhead cliche for good reason, it’s the bomb. The previous and following nights were good too.

9/3/77 Englishtown, NJ

12/29/77 Winterland

12/26/79 Oakland Auditorium

Any version of “Dark Star,” “Morning Dew” or “The Other One” is going to be worth a spin.

The best official Dead albums by far are all from 1970: Live/Dead, American Beauty and Workingman’s Dead.

Blues For Allah is good too, if you like the weirder, more spaced-out stuff. The live album One From The Vault is Blues For Allah performed in front of an audience, mixed in with some Dead classics, played as well as they ever got played.

The Dead did a good live “unplugged” album called Reckoning. There’s a nice version of “Bird Song,” a tribute to Janis Joplin, who the band was friendly with. One of the saddest moments in the documentary Festival Express is a shot of Jerry and Janis, both so drunk they can barely speak, and Jerry is telling Janis how beautiful she is, and you know how soon after that she’ll be dead.

The Jerry Garcia Band released an eponymous double live album in 1990. Jerry was a lot more enthusiastic about his side band than about the Dead at that point. The album includes some great material, ranging from the Band to the Beatles to Peter Tosh to Hoagy Carmichael.

Europe ’72 has a few choice cuts: “Cumberland Blues,” “He’s Gone,” “Tennessee Jed” which has some of Jerry’s funkiest playing, “Ramble On Rose,” “Jack Straw.”

Terrapin Station is seriously uneven, but it has a few tracks worth checking out. “Estimated Prophet” is a reggae tune in seven-four time, with many abrupt key changes. It sounds like a recipe for disaster, and yet it’s easily the best Dead song written post-1975. Bobby gives the lead vocal of his career, Jerry discovers envelope filter, the whole thing hangs right together. The other standout cut is “Samson And Delilah.”

In The Dark is interesting for including “Touch Of Grey,” the band’s only top ten hit. The high point is “West LA Fadeaway” which is within shouting distance of funky.

Update: check out this artwork made of cassette tape made by iri5. Nice pairing of subject and medium, don’t you think?

Nice commentary. But i can confirm from personal experience that the Dead were not taper friendly in the early ’70s. At one soundcheck i was literally chased around the stadium by their roadie Steve Parrish who wanted the tape after Kreutzmann pointed me out. They were pissed at the bootleg sales.

Beautifully written and some excellent insights! One correction, in your second graph,”I interviews” should be “In interviews” (no biggie but passes spell check) – also, I live near the remaining band members, and have worked for/with them over the decades, I made their first ever digital recording, have installed audio/video in their homes etc, and Bobby now is part owner of Sweetwater Music Hall in Mill Valley, while Phil has Terrapin Crossroads in San Rafael a few exits up 101, they both play there and sit in frequently with others, so I’ve heard “Not Fade Away” many many times over the years. It seems to me that they’ve slowly mutated to the final verse being a more understandable and grammatically correct “(A) love that’s real’ll not fade away” (sometimes leaving the “A” out). Or is it a mondegreen? Anyway, you’re both a good listener AND a good writer, this was fun!

Thank you! Great site! The Dead and Jerry’s playing made it possible for me to understand and open up to jazz. Thank you for reminding me of their importance.

Thanks for commenting. I probably would have found my way into jazz eventually without being pushed by Jerry, but it would have taken me many more years, and I’d be poorer as a result.

Iri5 is an awesome artist!!!

Thank You for sharing!

Rhondda Rhondda

I dig all those tape images he does. Thanks for writing.

Rock on.