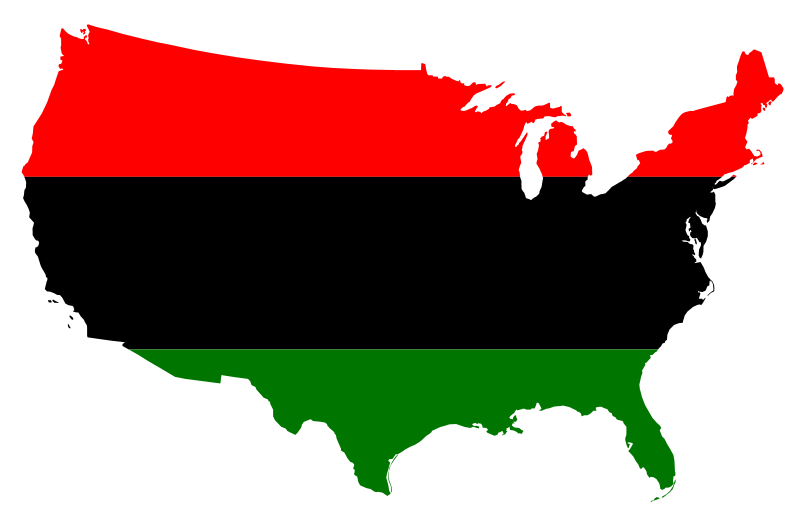

I have struggled for years to articulate why I like the music descending from Africa so much better than the music descending from Europe. I’m a typical American in this respect. Every genre that the mainstream enjoys takes its rhythms and loop structures from the African diaspora: rock, hip-hop, and EDM, of course, but country too, and pop, which blends together all of the above. The music academy remains firmly rooted in the Western European classical tradition, but even in Europe, popular music is dominated by loops of heavy percussion. Why?

Timothy Brennan gives a compelling answer in his book Secular Devotion: Afro-Latin Music and Imperial Jazz. White dudes like me are attracted to the music of the African diaspora because it’s a way for us to unconsciously enact traditional African religious practices. And why would we want to do enact African religious practice? Because it helps us resist Judeo-Christian morality and industrial capitalism.

Brennan lays out his main arguments in this interview.

New World African religion presents itself under cover, and as a matter of form rather than content, and so it comes off as secular, and not religious at all. African spirituality in today’s music, in any case, is not what is generally meant by the word “spiritual.” Music is devotion in African religion. Its value system is rooted in relaxation, sexual release, collective oral expression, and satire. All of these are deliberately posed, I am arguing, against the discipline and orthodoxy of Judeo-Christian modernity, which listeners fully understand in the hearing of it.

[T]here are dimensions of popular music (its appeal, how it circulates, its social role) that tell a hidden history of the imperial past… [T]he politics of popular music, unlike what many today argue, is not found in transgressive underground youth cultures (with which it has been closely associated by numerous critics since at least the rock invasion of the 1960s and 1970s). If music is subversive, it is because of the traditional and conservative gestures of the African religious element. That’s one element of the imperial past I am referring to. But there are others. The prevalent idea, for example, that the West is culturally superior to the rest of the world is in part based on the belief that literature is superior to music. Countries in which music is the primary expressive mode are considered backward, involved in mere pastimes, and unserious.

[H]ip-hop arose when it did in order to make up for a lack in U.S. neo-African music as compared with its Latin counterparts… We like to think of hip-hop as a heroic creation of embattled black youth with their backs to the wall, and of course it is. But it also had to be created in order to fill a void in African secular devotion.

[E]ven enjoyment and leisure can be forms of protest when they bring us face-to-face with the clashing outlooks of former colonial encounters that are continually replayed in code, and at the level of musical form. People never entirely forget the traumas of the past. They are looking for salvation from the dreary pursuit of spoils. The African presence in the new world has found a way to live, and is profoundly ethical in its resistance to the big commercial now. In a world of religious extremes, it gives us a different kind of ritual – the rituals of secular pleasure.

All of this rings true to me. I want to reject colonialism by identifying with the colonized. I want my soul to be educated by them. This is heavily on my mind right now, because today is Columbus Day. I find the existence of this holiday shameful. Jon Schwarz says that Columbus Day Is The Most Important Day Of Every Year.

Columbus’ landfall in the Western Hemisphere was the opening of Europe’s conquest of essentially all of this planet. By 1914, 422 years later, European powers and the U.S. controlled 85 percent of the world’s land mass.

White people didn’t accomplish this by asking politely. As conservative Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington put it in 1996, “The West won the world not by the superiority of its ideas or values or religion … but rather by its superiority in applying organized violence. Westerners often forget this fact; non-Westerners never do.”

In fact, European colonialism involved a level of brutality comparable in every way to that of 20th-century fascism and communism, and it started with Columbus himself. Estimates of the number of people living on the island of Hispaniola when Columbus established settlements range from 250,000 to several million. Within 30 years of his arrival, 80 to 90 percent of them were dead due to disease, war and enslavement, in what another Harvard professor cheerily called “complete genocide.” Contemporary accounts of the Spaniards’ berserk cruelty really have to be read to be believed.

Formally, of course, European colonialism largely ended in the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s. Yet informally, it has — behind the mask of what Pope Francis recently called “new forms of colonialism” — continued with surprising success.

Thus European colonialism is the central fact of politics on earth. And precisely because of that, it is almost never part of any American discussion of politics. Anthropologists call this phenomenon “social silence” — meaning that in most human societies, the subjects that are core to how the societies function are exactly the ones that are never mentioned.

If we maintain the social silence around colonialism, our past and present will always be bewildering, like the above list. But if we break the silence, and talk about what truly matters, the confusing swirl of war and conflict can suddenly makes sense.

You can’t engage seriously with any kind of American popular music without learning about where it came from, and you can’t learn about Africa or the Caribbean without coming into contact with the disgusting history of imperialism. I might be a beneficiary of that imperialism, but I don’t have to perpetuate it.