Bennett, J. (2011). Collaborative songwriting – the ontology of negotiated creativity in popular music studio practice. Journal on the Art of Record Production, (5), online.

My professional life at the moment mostly consists of teaching classical and jazz musicians how to write pop songs. While every American is intuitively familiar with the norms of pop music, few of us think about them explicitly, even trained musicians. It’s worth considering them, though. While individual pop songs might be musically uninteresting, in the aggregate they’re a rich source of information about the way our culture evolves. Joe Bennett describes popular song as an “unsubsidized populist art form,” like Hollywood movies and video games. The marketplace exerts strong Darwinian pressures on songwriters and producers, polishing pop conventions like pebbles being tumbled in a river.

Bennett lists the most common characteristics of mainstream hits:

- A first-person sympathetic protagonist/s, portrayed implicitly by the singer

- Repeating choruses, usually containing the melodic pitch peak of the song, summarizing the overall meaning of the lyric

- Rhyming, usually at the end of lyric phrases

- One, two or three human characters (or a collective ‘we’)

- An instrumental introduction less than twenty seconds long (though DJ/club versions can be longer)

- Lyrics that relate thematically to (usually romantic) human relationships, and that include the song title, usually in the chorus

- Melody lying in a two-octave range from bottom C to top C (C2 to C4), focusing heavily on the single octave A2 to A3

- Underlying four, eight, and sixteen-bar phrases, with occasional two-bar additions or subtractions

- Verse/chorus, core/breakdown, or AABA form

- 4/4 time

- A single diatonic or modal key throughout (the occasional truck-driver modulation notwithstanding)

- Length between two and four minutes

Bennett also boils down the history of Anglo-American popular songwriting into “a surprisingly small number of collaborative models.”

- Nashville: two writers using acoustic guitars and/or piano, pencil and paper, and not much else. There is usually a disciplined workday schedule. Lennon and McCartney worked this way, at least in the early years.

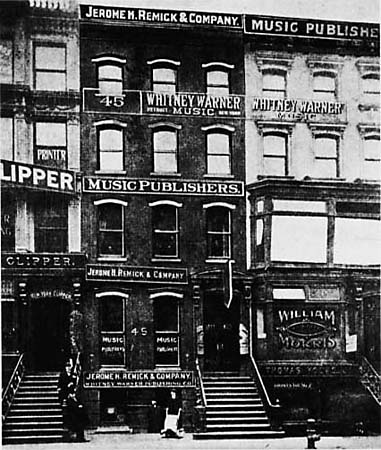

- Factory: A geographical location with staff songwriters, like Tin Pan Alley, the Hit Factory, the Brill Building, and Xenomania. Like the Nashville model, uses a regimented schedule. Very often attached to recording studios.

- Svengali: an artist paired with a more experienced “behind the scenes” co-writer. Think Max Martin or Dr Luke.

- Demarcation: a composer sets the work of a lyricist (e.g. Elton John and Bernie Taupin), or a lyricist writes to music by a composer (e.g. Johnny Mercer and Henry Mancini). Songwriting teams might also split melody and harmony, or drum programming and harmonic material.

- Jamming: a band generates ideas through semi-structured improvisation during rehearsal or recording sessions. Bennett cites U2 as using this model.

- Top-line writing: a producer supplies a completed backing track to another writer, who creates the melody and lyrics. This is a common model in current pop; see the example of Stargate and Ester Dean.

- Asynchronicity: collaboration between two people who are not in the same place, working at the same time. The top-line and demarcation methods are usually carried out this way, though the roles do not have to be so clearly defined. The Postal Service got their name because the members mailed each other DATs of work in progress, though now the more usual technique is to swap audio files or Digital Audio Workstation sessions online.

Technology has always shaped songwriters’ creative output. If you’re writing at the piano with sheet music as the ultimate product, you’re naturally going to focus on the aspects of the music that can be played on the piano and represented on paper: lyrics, melody, harmony. You’re probably not going to be overly concerned with arrangement or recording. It’s strange to imagine this now, but the sheet music industry was bigger than the recording industry through the 1950s.

The move from piano-centric writing to guitar-centric writing changed the sound of music as well. Guitarists are usually less formally trained than pianists, so their harmonic approach is simpler, though also less bound by convention. Guitarists favor power power chords and harmonic parallelism generally, leading to naively adventurous progressions like the minor seventh chords a minor third apart in “Light My Fire” by the Doors.

Computers have had some powerful impacts on songwriting conventions too, some obvious, some subtle. Bennett points out that many dance tracks of the 1990s have a tempo of exactly 120 beats per minute, because that’s the default tempo of Cubase and other widely used Digital Audio Workstations. Instrumentalists tend to write at slower tempos that are more comfortable to physically play, whereas drum loops usually inspire writers to choose faster tempos.

The most profound impact that computer-based production has had on pop songwriting is the near-total hegemony of loop structures, where the song’s entire harmony consists of three or four chords repeated in two, four, or eight bar loops. Loop structures, says Bennett,

are noticeably more common in contemporary UK pop than they were in the equivalent 1960s charts, and they are in turn more common in artists working in computer-based genres (R&B, Hip-Hop) than in band-based artists. To return to our current (October 2010) top 5 UK singles, four are based almost entirely on four-chord loops; one is based on a three-chord loop.

The loop-based production paradigm has strongly influenced instrument-based songwriting as well.

Interestingly, the specialist rock chart for the same week shows similar looping characteristics in three of the top five songs, the two exceptions being reissues of songs composed before music software was in common use by songwriters.

Partially this is because rock musicians hear the same pop music that the rest of us do, but I suspect the real reason is the common digital studio practice of listening in loop mode. While working on a particular section of a song, you typically set it to loop endlessly, rather than starting, stopping and rewinding over and over. It’s only natural that this listening experience would begin to exert an influence on the creative process outside the studio.

The jumping-off point for songwriting has historically been a fragment of lyric or melody, or a chord progression. In the computer era, the impetus can just as well be a drum loop or synth timbre. Rihanna’s 2007 hit “Umbrella” famously includes, and was possibly inspired by, a factory-supplied drum loop sample in GarageBand. As the pop mainstream becomes ever more synonymous with hip-hop and dance music, sound itself becomes the major creative driver, rather than harmony or melody.

Since Bennett wrote his paper, pop songs have become so driven by drum and synth timbre as to forego almost all other musical content. One of the biggest songs of the past year was the startlingly minimal “Turn Down For What” by DJ Snake and Lil Jon. Its lyrics defy all of the conventions listed at the beginning of this post; it barely has lyrics at all.

Would a Brill Building songwriter even recognize this as a “song” per se? Maybe not, but the American pop audience certainly does. “Turn Down For What” is unusual, but it might represent the beginning of a broader trend. Last year saw the equally huge and improbable success of “Hot N****” by Bobby Shmurda, which, unlike most popular hip-hop songs, has no chorus or hook. This kind of aggressively stark DJ-oriented music may well come to represent the pop mainstream as completely as Svengali-backed teen pop stars do now. If so, Bennett’s list of conventions will look very different a generation from now.

“Would a Brill Building songwriter even recognize this as a ‘song’ per se?”

True that the vocal is not very song-like, and there are no chord changes.

But there are very clear and catchy melodies in the instrumental, and it is structured like a pop song. While the bass, rhythm and the choice of digitized timbre for the instrumental define the feel of the song, I don’t think you could take out those instrumental melodies and still have something other than underscore.